Excy Hansda: Navigating Archival Fieldwork in Mumbai: Challenges, Opportunities, and Positionality

A few months ago, I finished my fieldwork for my PhD research in Architectural History. My research investigates the microhistories of the middle-class Indians who moved to the suburbs of Bombay in the early twentieth century and the kind of spaces they lived in. Looking at a postcolonial angle, I am interested in questioning the colonial suburban vision and by highlighting the Indian agency in shaping the suburban urban housing projects, neighbourhoods and their dwellings in late-colonial Bombay. This blog reflects on the challenges and opportunities I encountered while conducting fieldwork in Mumbai. As an Indian PhD scholar based in England, fluent in both English and Hindi, I found that my position brought unique advantages and complications to archival research in Mumbai.

I have prior experience working in archives in both the UK and India. I quickly realized that my background—an Indian architect affiliated with a British academic institution working on a historical subject—often piqued interest in my project. Despite the initial curiosity my profile evoked, I was one of hundreds of Non-Resident Indians (NRI) affiliated with overseas institutions, and this seldom translated into privilege. If anything, being a North Indian, I was seen as a foreigner in Mumbai. Accessing senior bureaucrats in archival institutions and getting information smoothly and efficiently remained particularly difficult.

Finding the Right Archives

I began “getting the data” early in my PhD (February 2023), in parallel with my literature review. I started with the India Office Records at the British Library in London and expanded my search to include collections at the Liverpool School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the School of Oriental and African Studies, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the National Archives at Kew, and others. I investigated diverse sources—Annual Administrative Reports, maps, manuals, and published books. However, due to the hyper-specific focus of my study, initial results were limited.

This led me to change my methodological approach. I revisited the literature and drew on approaches from disciplines such as cultural studies, English literature, and sociology. This led me to explore unofficial sources such as online newspapers, Town Planning Review and the Journal of the Indian Institute of Architects at the Royal Institute of British Architects Archives in London. This helped me expand my knowledge of my subject.

My first fieldwork trip to Mumbai (January 2024) opened a new chapter. I visited the Maharashtra State Archives (MSA) at Elphinstone College, Mumbai, where I discovered files rich in minute detail—memos, petitions, letters, advertisements, maps, municipal debates, and more—everything useful for my research, unlike the colonial records in London, which largely included annual administrative reports and policy documents of the colonial bodies like the Bombay Improvement Trust and the Bombay Development Department, the Mumbai archives revealed the voices and subjectivities of local Indian residents who contested colonial policies and many cases of negotiations, contestations and even micro-scale conflicts which were often absent from official reports.

Missing Records and the State of Archives

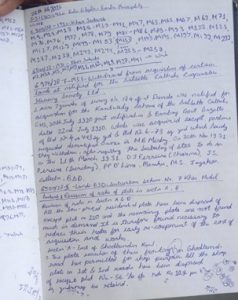

Accessing the archives was not easy. The MSA, one of India’s oldest surviving archives, is poorly maintained and has limited funds. Files are deteriorating, and storage conditions are far from ideal. The reading room is small and dusty, with limited hours—open only five days a week, six hours per day, with an hour-long lunch break. Visitors can request just five files a day. The retrieval process is slow (waiting over two hours is common). Photography is not allowed, and one must request Xerox (Fig 1) or scanned copies, which are payable only in cash. Getting Xeroxes can take 20 days or more; scans may take months. (I am still waiting for the scans that I requested in February) Therefore, I resorted to transcribing the files and making notes (Fig 3 and 4).

Many records are missing. Files before the 1920s are largely uncatalogued and are organized as volumes for entire years for each department of the archives (Revenue, Judicial, PWD, General). Finding specific content means reading through these thick volumes page by page. For post-1920s material, although some cataloguing exists, it’s often incomplete. These are specific files which are numbered, and the numbers correspond to the numbers present in the hefty indices. One has to go through the indices in order to find the files.

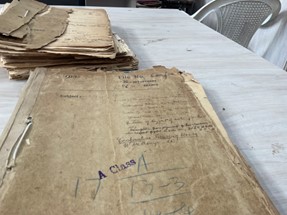

Once a file is located, an office peon brings it—after dusting it off (Fig 2). Some are missing completely, and the office peons cannot find them. Others are in fragmented conditions, so they cannot be accessed. While others have missing maps or pages which are crumbling into fragments.

Fig 1: Xerox of a page in a file located at the MSA

Fig 2: A File on Co-operative Housing Society at the MSA

Fig 3 and 4: Transcriptions and Notes I made based on information available in archival documents at the MSA

Finding Sources

A central database for archival material simply does not exist. I relied heavily on human networks: clerks, peons, research assistants, historians, archivists, and fellow researchers. Often, they directed me to smaller archives—usually cramped rooms within municipal offices—where old documents were kept in poor condition and disorganized bulk.

At the MSA in Elphinstone College, I was directed to the Old Customs House in Mumbai. There, I learned they only housed records from Bombay City, so I was redirected to the archives at the Municipal Corporation Office of Bombay Suburban District in Bandra, only to be told that my time period of interest was not covered. Eventually, I was pointed toward ward offices, municipal boards, and local talathi (village record) offices.

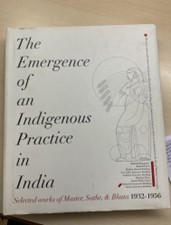

Due to reorganization across the colonial and post-independence eras and the separation of districts and provincial state, records have been scattered. The only way to find them is through local knowledge—gathered from seasoned researchers, administrators, or office staff. Sometimes, I stumbled upon data in unexpected places, such as the Dadar municipal archives or the Art Deco Mumbai Society, which provided helpful secondary sources in English and vernacular languages (Fig 5 and 6).

Fig 5 and 6: Books obtained at the Art Deco Mumbai Trust, Mumbai

The reception of these archives was also varied. Sometimes, the staff was friendly and gave me access to files, right after I showed him my ID card and university letters. In other cases, I was made to wait for half an hour before meeting the upper bureaucrat. Sometimes, I had to follow up several times before they granted me permission to visit their archives. This was the case of Municipal Corporation archives, Mumbai.

Navigating the Neighbourhoods

Beyond archives, the buildings themselves served as vital secondary sources. Many twentieth-century buildings had been demolished, redeveloped, or repurposed. Some stood vacant; others had been converted into commercial spaces, with original residents gone.

Identifying buildings from the 1930s–40s required searching for buildings with style, typology and aesthetics matching that of the 20th-century architecture of Bombay. I used secondary literature available on Mumbai, tips from fellow researchers and architects working in Mumbai, detailed reports from the Mumbai Metropolitan Region – Heritage Conservation Society (MMR-HCS), and a database created by Art Deco Mumbai Trust to search buildings. These contained valuable mapping and description of old historic surviving buildings with histories of ownership, years of construction, sketches, photographs, and drawings. I used these for site observations and photographing the exteriors of the building (Fig 7 and 8)

.

Fig 7 and 8: Walking in the suburban town of Khar, Mumbai as a Method to Collect Data

However, accessing the interior of the buildings was a different challenge. I was often accompanied by a local Marathi-speaking friend to help communicate. His surname “Patil”, which is common in Mumbai, could have helped me start a conversation with the local residents of Mumbai suburbs- so I thought. Residents were tight-lipped, asking questions like “Kahan rehte ho?” (Where do you live?), “Marathi nahi aati kya?” (Don’t you know Marathi?), and “Kya dharam/jaat/surname hai?” (What’s your religion/caste/surname?). These euphemistic inquiries exposed the enduring social divisions of caste, class, and religion—reminding me that while buildings and built fabric might have changed, social fabrics and the mindset of the people are just the same as in the 1930s-40s Bombay.

Language

In the scrutiny of archival works, language skills were sometimes difficult. Language agitation and violence in the name of protecting Marathi culture and identity are common in Mumbai and the provincial state of Maharashtra, where outsiders are forced to speak in Marathi. However, most of the time, people were helpful to me in finding the source materials. The historians in academic and non-academic institutions were proficient in English, Hindi, and Marathi, and they helped me with ideas for my projects. People, especially those working in lower bureaucracy, were able to speak Hindi and directed me to people and places where I could retrieve information.

Logistics of Living in Mumbai

One has to find the right months to work in Mumbai. Working in August was not ideal. The intense humidity and monsoons made things spectacularly difficult. Working in summer could be difficult as well, as the heat is intense and the humidity is dangerously high. Working during the winter is better, though it is mosquito season. I lived in Vasai, a northern suburban town outside Mumbai, and used to commute on a local train two hours away from the archives, which was at the final southern station of Bombay city. Just like what I wanted to study, I lived like a middle-class person who lived in the suburbs and commuted to the city to make ends meet.

Final Reflections

Someone who works at, for example, the British Library or the Biblioteque Nationale, would not expect this set of challenges. These challenges included obtaining sources of information from beyond the archives, pursuing people to find information, and collecting data in sometimes un-welcoming environments, for which one needs to have a different approach towards them. Being a people’s person and being street-smart helps. Networking and making connections with people make things easier and give you access to a substantial amount of information. Whilst there were complications, it was an enriching experience, making me skilled in finding sources of information, connecting dots, finding and sometimes creating a thread, and keeping backup plans ready. Here, adaptability and patience helped. Having relationships with people has helped me more than having any institutional affiliations,

Fig 9: The sign board at the local railway station from where I boarded the train to the archives, every morning

Fig 10: The family with their neighbours with whom I lived in Mumbai suburbs

Finally, although having friends-like family in Mumbai and its suburbs made me somewhat familiar with the city, however being a North Indian, miles away from Mumbai, I am sure I might not have noticed a lot of subtleties both inside and outside the archives and sites of inquiry. On the other hand, as a scholar based in England, I found certain information in files, ideas, or simply the way of living striking, which Mumbaikars would have taken for granted. I am indebted to the Patil family and my friends at IIT Powai, where I imposed myself for a significant time period. Also, my colleagues who I knew before and the ones whom I met at the archives helped me point out interesting details, showed me directions during this fieldwork, and accompanied me on several site visits. These certainly positioned me in how I was looking at the sources, the archives, the people, the suburbs and the city.

0 Comments